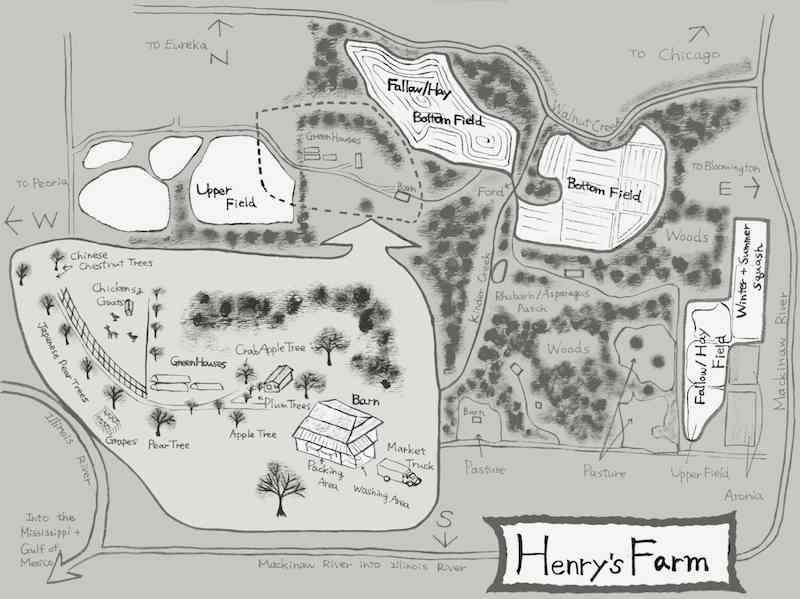

Map by Hiroko K. Brockman

Each year, about half of Henry's 25 acres is used to grow vegetables, and half is fallow. Half of both the bottomland fields and the upper fields is allowed to rest and regenerate for two years, while the other half produces vegetables. The fallow land is planted in an alfalfa hay mixture, which is cut a few times a year and used for mulch and for the animals.

More importantly, legumes in the hay mix put nitrogen back into the soil, and the fallow years allow the soil microbes and fungi to re-establish themselves, and create a healthy, living (and giving) soil.

Every harvest day, wave after wave of freshly picked produce makes its way by the pick-up-load from the fields to the packing shed. There, everything is washed, sorted, boxed, bagged, and loaded on the big truck for delivery to our local CSA members or to our Evanston Market customers.

What We Grow

Henry loves variety, and grows vegetables from all over the world including heirloom varieties. An "heirloom” vegetable is generally described as a variety that has a long history of human use. American heirlooms generally can be traced to crops grown by Native Americans or seeds that immigrants brought with them to the U.S. and then grew year after year in their backyards, collecting seeds each year to plant the next. If you want a tomato to taste like a tomato, you have to go back to the older hybrids or the heirloom varieties, which are not uniform in size or shape or color, not very transportable, and not long-lasting on the shelf. Instead you get flavor, flavor, flavor!

If you’re interested in growing some heirloom vegetables, a good source SeedSavers Exchange.

A list of 600+ Vegetables We Grow

Click on a vegetable type to see the cultivars we grew in 2012. We experiment with a few new cultivars every year, but the number of cultivars we grow holds steady.

FYI an "OG" after a name means organic seed: We buy it whenever possible.

Explore a bit and you’ll find we grew 89 tomato, 49 pepper, and 23 corn cultivars.

Dragon Tongue OG

Fresh Pick OG

Gold Rush OG

Greencrop

Henderson Bush

Indy Gold OG

Jade OG

Jumbo OG

Maxibel OG

Provider OG

Purple Podded Pole OG

Red Noodle

Tavera OG

Agate Pinto OG

Black Turtle OG

Calypso OG

Jacob’s Cattle OG

Light Red Kidney OG

Taylor Dwarf Hort.

Vermont Cranberry

BeSweet 2001

BeSweet 2015

Butterbeans OG

Midori Giant

Sayamusume OG

Shirofumi OG

Tankuro OG

Floriani Red Flint OG

Hopi Blue Flower

Painted Mountain OG

Roy Calais Flint

Butter- Flavored OG

Dakota Black OG

Pennsylvania Dutch

Red Beauty OG

Robust 1284H

Smoke Signals OG

Augusta

Cameo-Untreated

Fleet

Honey Select

Incredible RM

Lancelot

Luscious OG

Rose Potpouri OG

Ruby Queen\Silver Queen

Spring Treat

Sugar Buns

Sugar Pearl OG

Sumptuous

Amethyst Improved OG

Aroma 2 OG

Christmas

Genovese OG

Mixed Specialty

Mrs. Burns Lemon

Sweet Thai OG

Caribe OG

Santo OG

Cutting Celery

Par-Cel

Fernleaf

Greensleeves OG

Hercules

Orion F1 OG

ZefaFino

Dark Green Italian OG

Krausa

Green Shiso

Red Shiso

Epazote OG

Papalo

Stevia

Australe

BarbadeiFrati

Boulder OG

Brown Golding OG

Cardinale OG

Coastal Star OG

Cocarde OG

Concept OG

Cracoviensis OG

Crispino OG

Dark Green Romaine OG

Dark LolloRossa OG

Double Density OG

Flashy Butter Gem OG

Flashy Green Butter Oak OG

Forellenschluss OG

Green Star OG

Hussarde OG

Jester OG

Kalura OG

Kiribati

Lettony OG

Merlot OG

Merlox Red Oak OG

Merlox Summer Crisp OG

New Red Fire OG

Olga OG

Optima OG

Oscarde OG

Outstanding OG

Panisse

Pirat OG

Plato II OG

Red Cash OG

Red EaredButterheart OG

Red Iceberg OG

Red Sails OG

Red Tide OG

Rouge d'Hiver OG

Skyphos

Speckled Amish OG

Sweet Valentine OG

Sylvesta OG

Tropicana OG

Ubriacona

Waldmann's Dark Green OG

Winter Density OG

Yugoslavian Red OG

Ambrosia F1

Goddess F1-untreated

Halona F1

Hannah’s Choice F1

Honey Pearl

Lil' Loupe F1

Orange Sherbert F1

Sarah's Choice F1

Savor F1

Sugar Cube F1

Tirreno F1 OG

White Honey

Au Golden Producer

Cathay Belle F1

Crimson Sweet OG

Gold Flower f1

Sangria

Dark Star

Little Baby Flower

Mickylee

New Orchid F1

Petite Yellow F1

Sorbet Swirl F1

Sunshine F1

Laxton's Progress #9

Mayfair OG

Green Arrow OG

Dwarf Grey Sugar

Mammoth Melting OG

Oregon Giant OG

Oregon Sugar Pod II

Cascadia OG

Sugar Ann OG

Sugarsnap OG

Sugar Daddy

Big Red Ripper

Carwile's Virginia

Pinkeye Purple Hull

Queen Ann Blackeye

Schronce's Deep Black

Tennessee Red Valencia

Virginia Jumbo

Bianca F1

Catriona F1 OG

Chocolate OG

Flavorburst F1

Golden Cal Wonder OG

Gourmet F1

Islander F1

Jumbo Sweet F1

Lido Lamuyo F1 OG

Lipstick OG

Purple Beauty OG

Amish Pimiento OG

Antohi Romanian OG

Belcanto F1 OG

Carmen F1 OG

Feherozon OG

Fushimi

Mellow Star F1

OranosF1 OG

Padron

Piemonte Pepperoncini OG

Pimenton de Espellette

Tangerine Pimiento OG

Xanthi F1 OG

Aji Colorado OG

Aji Cristal

Conchos F1

Corcel F1

Czech Black OG

El Jefe F1

Hidalgo OG

Highlander F1 OG

Holy Mole F1

Hot Portugal OG

Jalafuego F1

Magnum OG

New Mexico Joe E Parker OG

Red Rocket OG

Red Rocoto

Ring of Fire OG

Sahuoro

Tiburon F1

Triunfo F1 OG

Bell Boy F1

New Ace F1

Olympus F1 OG

Orion F1 OG

Red Knight X3R F1

Revolution F1

Adirondack Red OG

All-Blue OG

Austrian Crescent OG

Bintje OG

Canela OG

Carola OG

Colorado Rose OG

Dark Red Norland OG

Desiree OG

Elba OG

French Fingerling OG

German Butterball OG

Irish Cobbler

Kennebec OG

Mountain Rose OG

Purple Peruvian

Red Maria OG

Red Thumb OG

Rio Grande Russet OG

Yukon Gold OG

Benning's Green Tint OG

Bush Baby F1

Costata Romanesca OG

Eight Ball F1

Gentry F1

Gold Rush F1

Goldy F1 OG

G-Star F1 OG

Magda F1

Midnight Lightning OG

Mulitipik

Raven F1

Dunja F1 OG

Sebring

Success

Teot Bat Put F2

Yellow Crookneck OG

Yellow Scallopini F1 OG

Y-Star F1 OG

Zephyr F1

Black Forest OG

Cha-Cha F1

Confection F1

Crown Pumpkin

Delicata JS OG

Eastern Rise F1

Honey Boat OG

Honey Nut OG

JWS 6853 PMR F1

Kurinishiki F2

Marina di Chioggia

Metro PMR F1

Nutterbutter OG

Paydon OG

Pinnacle F1

Ponca Baby OG

Small Wonder F1

Squisito OG

Sugar Dumpling OG F1

Sunshine F1

Sweet Dumpling OG

Sweet REBA Bush OG

Tiptop PMR F1

Tivoli F1

Tuffy OG

UchikiKuri OG

Waltham Butternut OG

Zepellin Delicata OG

Black Cherry OG

Chadwick Cherry OG

Golden Sweet F1

Green Doctors Frosted OG

Indigo Rose OG

Peacevine OG

Red Pearl OG

Sakura F1 OG

Snowberry

Sun Gold F1

Tomoatoberry Garden F1

Toronjino F1 OG

White Cherry OG

Aunt Ruby's German Green OG

Beefmaster F1

Beryl Beauty

Black Prince OG

Brandywine OG

Burgess Stuffing

Cherokee Purple OG

Chocolate Champion

Costoluto Genovese

CostolutoFiorentino

Emerald Green

German Johnson OG

Goldie OG

Green Zebra OG

Hungarian Heart

Jade Beauty

Japanese Black Trifele OG

Jubilee OG

Kosovo

Martha Washington F1 OG

Marvel Striped OG

Momotaro F1

Moon Glow OG

Mr. Snow

Nyagous OG

Orange Oxheart

Pineapple OG

Ponderosa Red OG

Prudens Purple OG

Purple Calabash

Red Brandywine OG

Red Pear Piriform OG

Red Zebra

Rose de Berne OG

Rosso Sicilian OG

Schimmeig Striped Hollow OG

Striped German OG

Stupice OG

Summertime Green

Tansmanian Chocolate

Topaz or Huan U

Trophy OG

Violet Jasper orTzi Bi U

Wapsipinicon Peach OG

Yellow Brandywine OG

Black Icicle

Black Plum OG

Debarao OG

Mr. Fumo OG

Opalka OG

Orange Icicle

Pink Icicle

Speckled Roman OG

Yellow Icicle

American Original F1

Better Boy F1

BHN-1021 F1

Big Beef F1

Bobcat F1

Celebrity F1

Dafael F1

Defiant PhR F1 OG

Emperador F1

Golden American Original

Jet Star F1

New Girl F1

Tangerine American Original

Valley Girl F1

Granadero F1 OG

Monica OG

Toma Verde OG

Verde Puebla OG

Why Join Henry’s CSA?

You’ll eat with the seasons, and get the most delicious and nutritious produce possible!

Eating with the seasons means eating what is happiest…when it is happiest. And I honestly think that makes you and your body the happiest, too.

You’ll be helping to save the world one delicious bite at a time!

By joining my CSA, you become a fighter against the current high-consumption, high-waste civilization that is ravaging our planet. As consumers of food grown in a sustainable way, you are initiators of a circle of health that extends from you to the entire planet. Eating my highly nutritious food makes you healthier, and it also makes my farm healthier. And my healthy farm makes the larger ecosystem surrounding it healthier, and that makes our entire planet healthier. And it all starts with you and each forkful of food you eat. So, join the CSA—help save the world!

It’s a great deal--the most reasonably-priced you’ll find!

Not only are we the least expensive CSA around, but our 26-week season is one of the longest in the Midwest. Make sure to compare the per-week cost when comparing CSAs.

You can customize what vegetables you receive each week.

I do this in a number of ways. First, I build choice into the weekly list of produce, often providing a choice of two or more different roots (e.g. beets or carrots), herbs (parsley or dill), and/or greens (lettuce or mesclun salad mix or arugula). In addition, downstate CSA members may use the Exchange Table, while Evanston CSA members have a generous substitution policy.

What You Get

Fresh-picked seasonal vegetables for 26 weeks, starting the last Tuesday in May and ending the middle of November. The selection of produce varies from week to week (see typical shares below), but usually you‘ll fill a bag to overflowing with 7-9 types of vegetables at the peak of their flavor.

Best taste and highest nutritional value. We grow only the best-tasting varieties and food scientists have shown that Taste = Nutrition!

No GMOs, Pesticides, Herbicides, or Synthetic Fertilizers

Convenient Weekly Pick-ups of vegetables picked that very day. The produce we hand-picked at 7 in the morning is in your hands that evening, after traveling 20 miles or less to reach your table. Pick-up locations are in Bloomington, Eureka, Morton, Peoria, and on Henry's Farm in Congerville. See location details below.

CSA Pick-up Locations and Times

You pick up your CSA shares each Tuesday for 26 weeks starting the last Tuesday in May at these locations:

Bloomington/Normal: Pick-ups are between 6:00 and 7:00pm at the Unitarian Church parking lot at 1613 East Emerson Street in Bloomington. Starting the first Tuesday in October they move indoors to the Vitesse Cycle Shop at 206 South Linden, Normal and run from 6:30 to 7:30pm.

Eureka: Pick-ups are between 5 and 5:30pm

Morton: Pick-ups are between 6 and 6:30pm.

Peoria:

Central Peoria: pick-ups are between 4:30 and 5:30pm.

Near Peoria Heights: pick-ups are between 5:30pm and 6:30pm.

Congerville (on-farm): Pick-ups are after 3pm at 432 Grimm Road.

Didn't pick up your CSA share on Tuesday?

You can pick it up on Wednesday at Henry's Farm. Be sure to text him before noon to let him know you'll be picking it up. Here are detailed instructions on how to get to Henry's Farm and what to do when you arrive.

Chicago Area: Pick-ups are between 6 and 10 a.m. in the Evanston Farmers Market (behind the Hilton Hotel on Maple Avenue) at Henry’s stand.

Typical CSA Shares

Spring

Lettuce

(Favorites like Oak Leaf and Romaine, as well as heirloom varieties)

Radish

Spinach

Green Onions

Broccoli

Chives

New Potatoes

Rhubarb

Summer

Tomatoes

(Beefsteak varieties, as well as heirloom varieties, plum, and cherry tomatoes)

Cucumber

Zucchini

Green Beans

Carrots

Corn

Kale

Basil

Fall

Winter Squash

(from Acorn and Butternut squash to the gourmet Delicata and the Japanese Kabocha)

Green Peppers

Sweet Potatoes

Fennel

Parsnips

Beet

Bok Choy

Muskmelon

Noun Project designers of black & white icons from which the above were derived: Baboon designs (spring radish), damar bintang (summer tomato), parkjisun (fall squash)

Prospective CSA Member FAQs

This is a difficult question to answer. Weight is not really a good measure because in the spring when you are getting lettuce, spinach and other light things a whole bag full of produce might not weigh more than a couple pounds whereas in the late summer when you are getting heavy things like melons, sweet corn and tomatoes you might lug home as much as 10 pounds of produce. Volume is not really a good measure either, but generally you’ll be able to fit a weekly share easily into two plastic grocery bags and some weeks it will fit in one if you really work at it.

The way I measure a weekly share is by value. When I decide what to give you each week, I make sure it comes to around $16.75 worth of produce (as of 2017) because that is what I am charging you for it. In reality, however, you almost always get more than $16.75 worth, because I think that you should get a better deal through the CSA than you would at a farmers market. A CSA member last year, for example, would have had to pay nearly 20% more if they would have bought all the produce in their share at the farmer’s market. And they were to have bought the same amount of all the vegetables in their share at the local Jewel or Kroger), they would have spent nearly twice as much – see FAQ #5 below.

The best way to measure a share is to say how many people it can feed. Unfortunately, this too is a very difficult question to answer because people’s dietary and cooking habits are so varied. However, most CSA members find that a share is adequate to feed a family of four “omnivores” or a family of two vegetarians. That said, I have had a family of two consume a double share and I have had two families of four members each share a single share. It really comes down to two factors: how often (how many meals) you cook at home as opposed to eating out or eating prepared dishes and how many vegetables you include in your diet.

Like the question above, the answer here is going to be different depending on your family’s dietary and cooking habits. However, for most families, I think the answer is no. You will probably find yourself buying a small amount of produce. There are a couple reasons for this.

First of all, it is difficult for me to grow some of the staple crops in large enough amounts at low enough cost. Potatoes, onions, and garlic are good examples. If you use these in most of your meals throughout the year, you will probably have to supplement what you get through the CSA by buying them elsewhere. That said, I am working on increasing my production of these crops so that I can cover more of the demand through the CSA. At the end of the season, you can tell me how I did and I will continue to produce more if needed for future years.

Second of all, I can only supply what is growing on my farm in that season. You are not going to get a tomato before late July no matter how much you or I want one. Personally, I hope that you won’t go out and buy a tomato before mine come into season. I encourage you to wait. If you are diligent about using and enjoying the produce in your share each week, you won’t even miss those tomatoes until it is time for them. And when that time comes, they will taste so much better for having waited for them.

So, although you might be tempted to buy produce out of season, my advice is to resist that temptation and really get into the act of eating seasonally.

Another reason you may buy supplementary produce is that you don’t get enough of some item in your share to make a dish you wanted to prepare. You wanted to make borscht (beet soup), for instance, but there aren’t enough beets in your share that week to make a big enough batch to feed the whole family. If you really have to have borscht that week, you are going to have to get more beets elsewhere.

But please remember, belonging to a CSA is all about flexibility. The CSA members who rejoin year after year are those who learn to roll with the seasons and roll with the share offering. If there are enough beets for borscht, they make borscht. If there aren’t, they make a cold beet salad with raisins and walnuts. Or they put those beets in the refrigerator until the next time beets are in the share and then have enough for a nice big batch of soup.

As you learn to be flexible and adaptable in your meal plans and eating habits, and learn how to prepare and eat what you have when you have it, you will find that you are buying less and less outside of what you receive in the CSA.

Finally, you may find that you just eat more produce in a week that what the CSA share provides. Well, congratulations! That means you have a very healthy diet, are skilled and versatile cooks, and eat most meals at home as a family. Unfortunately, you are the exception and I have to tailor the size of the CSA share to what a normal American family can consume in a week. The most common reason I get for members not rejoining my CSA is that there is too much in the share and they wasted too much of it.

If you are sharing your share with another family, next year please purchase your own share. If you are already a single family member, then please get a double share. I’ll offer you a discount on the second share. I love to encourage good eaters.

A

It’s better for the environment. (Please see “Save the world one bite at a time” above.)

Waste: There is essentially no waste of produce with the CSA. If I have 200 members in the CSA, I pick 200 bunches of beets and every one of those bunches is not only already paid for but every one of them will end up on a member’s dinner table. With the farmers market, I never know how many beets I will sell in a given week. If one week I underestimate demand and underpick, I lose money and produce that could have been sold goes to waste in the field. If the next week I overestimate demand, I’ve wasted time, labor and resources harvesting, washing, packing and hauling the produce unnecessarily and in the worst cases, end up having to throw extras away. This does not happen with the CSA.

Efficient management of the farm. This is perhaps where I as the farmer get the greatest value from the CSA. The fact that I as the farmer am able to decide each week what to harvest for the CSA makes my farm incredibly more efficient. It gives me the latitude to harvest crops exactly when they need to be harvested for best taste, best nutritional value, and best use of time and space. I can tailor my harvests to avoid crop losses due to pests, weeds, and inclement weather. The result is that little goes to waste and the farm is more sustainable and more environmentally friendly.

B

You’ll save money. (Please see “#3. It’s a great deal!” above.)

C

You’ll eat better. Joining a CSA is the best way to ensure that you will eat better. Despite your best intentions, you may find that it is hard to stick to the diet that you know is best for you—a diet high in vitamins, minerals, fiber and whole foods and low in fat, sugar, salt and processed foods. Not only will picking up a complement of vegetables each week make you more likely to actually prepare and eat more vegetables, but you will find the fresh produce so beautiful and flavorful that you will want to eat more vegetables.

Our handy recipe book and our many recipe ideas in the weekly email and on our website will make preparing the foods easier, too.

D

It’s an adventure. Even if you shop regularly at a farmers market, you probably tend to pick up the things that you are already familiar with and know how to cook. In the CSA, you are going to receive some vegetables or varieties that you have never even heard of before. We will give you suggestions on how to prepare everything we give you, particularly things that are a little unusual. After a season in the CSA, you’ll probably realize that some of your favorite vegetables are things you didn’t even realize existed before, whether it is arugula, Aunt Ruby’s German Green heirloom tomatoes or purple sweet potatoes.

E

It’s a great incentive to live better. Joining a CSA is kind of like joining a gym. If you are like most people, if you pay for a year membership at a gym you are going to end up exercising more regularly than if you had just made a general resolution to workout more. A CSA membership works the same way. You may resolve to eat better by shopping at the farmers market each Saturday, but chances are when push comes to shove you are going to end of missing a lot of farmers markets for a whole variety of reasons, many ones of convenience. When you join the CSA, you are locked in to picking up those vegetables every Tuesday no matter what, and you adjust your life accordingly. End result—you eat better and are healthier and happier.

F

It’s the best way to support a local farmer.

Every Monday evening we will email you the CSA Food and Farm Notes, which will list the produce you will pick up the following Saturday. This is the same email that goes out to my downstate CSA members, who pick up their produce on Tuesdays, so don’t be confused if you see references to Tuesdays, Bloomington/Normal, etc. (You may already receive the email that goes out to Evanston Farmers Market customers on Thursday, but please use the Monday evening email to find out what's in that week’s CSA share—it is clearly identified as the Henry’s Farm CSA email.)

We will pick your produce on Thursday and Friday.

On Saturday, come to the market between 6 and 10 a.m. with the list of the items in your share that week from the Tuesday email.

Check in with me. I’ll mark your name off the membership list and then we will go over the share list together. For example, say it is August and your list reads: sweet corn, tomatoes, cucumbers, zucchini, basil, beets and Swiss chard. I will say, “Okay, this week you get 4 ears of corn, 2 lbs. of tomatoes, 1 cucumber…etc.”

Walk through the stand picking up your items from the market display. In other words, it’s self-serve! The CSA produce will not be separated from the market produce and we won’t have your share pre-bagged for you. You will bring your own bag, pick out your produce from the display tables and bag up your own produce.

And you get to eat produce that is always at its absolute best--even if you aren‘t able to choose what you get.

Yes, often when you pick up your share you will be able to choose between some items. Usually, I do this for vegetables that I know from past experience that people either love or hate. Cilantro is a great example. People seem to either find it heavenly or disgusting, so the sign on the box might read, “Take one bunch cilantro or one bunch dill” and you get to choose what you want. Another example--some members look forward to geting hot peppers in their share but many members can’t eat them at all. So whenever I bring hot peppers, I always also have sweet peppers to take in their place. Almost every week there will be at least one choice like this in the share.

Sometimes, usually in late summer or early fall, I will bring in a whole range of vegetables to choose from. I’ll put up a big sign that says, “Take any 3 items from this table!” and you’ll have a choice of many different vegetables to choice from.

Of course, in all honestly, I have never met a vegetable that I didn’t like. Show me a vegetable you don’t like and I believe that between me, Hiroko, my sisters, my mother and mother-in-law, we can find a way to fix it that you will like. And you will find some of those recipes in each week’s Food and Farm Notes. On top of that you have our Henry’s CSA Recipe Book and the searchable archive of recipes on our website.

Finally, it is always a good idea to re-try those things that you “know” you don’t like. You may not like broccoli because your first experience was with those pale-green, rubbery stalks of overcooked broccoli served in the school cafeteria. Try the real thing--you may be delighted to find out what you have been missing.

Finally, the Exchange Table gives you some choice as well. See the next FAQ for how it works.

Full of bugs? No. Will you ever find an insect on your produce? Yes. You might find a corn earworm on the tip of your sweet corn one week for instance, or a cabbage worm in your broccoli now and again. But it will be rare. My philosophy is live and let live. I know some people are so squeamish that if they see a bug on a vegetable, they’ll throw the whole thing out rather than eat it, but I think that is silly and wasteful. Look at it this way. Say you have an earworm on your corn. Earworms come in at the tip of the ear and they eat the silks and the kernels at the very end of the ear. Now all you have to do take a knife, flick out the worm and cut off the tip of the ear. Voila! You have a perfectly good ear of corn.

The other alternative is to spray the corn with a toxin that will kill all the earworms in the field (and other life as well). As someone once said to me, "Would you rather have a worm that you can see or a poisonous chemical that you can’t?" Besides earworms and cabbage worms, few insects are dumb enough or slow enough to stick around after a vegetable is picked. Sometimes you will see the telltale signs of where insects have eaten a little of your produce before you got to it. Often the greens will have little holes in the leaves where flea beetles were munching or the beans will have some gnaw marks from bean beetles, but I see nothing wrong with sharing a little of our food with our insect brethren. Sometimes insects can feed so heavily on a crop that it’s no longer worth it to harvest or try to eat, but if the damage is only cosmetic I will go ahead and harvest and sell a crop with a little insect damage. I certainly won’t go out with insecticides (even organic insecticides) just to ensure the cosmetic beauty of a crop.

Remember, just two generations ago, before the rise of chemical farming, everybody dealt with insects and their handiwork everyday--and were healthier for it.

Our Farm’s Deep History

Geology isn't quite destiny, but it's close. Farming Henry’s way on Henry’s land has been made easier by its geological history.

Available water

Deep wells provide the water for all of the people and animals on Henry’s Farm. They also provide water for transplants, and during the rare times when irrigation is necessary to germinate seeds or keep plants going through droughts.

These deep wells are made possible by the aquifer under Illinois formed 570 to 250 million years ago when Illinois was covered by shallow seas (and located near the equator!). The sediments deposited in these seas later turned into the alternating shallow sedimentary strata of limestone, shale and sandstone. Sandstone provides excellent water quality: Small pores between grains of sand allow water to slowly move through the rock while filtering out impurities.

Poor suitability for industrial farming

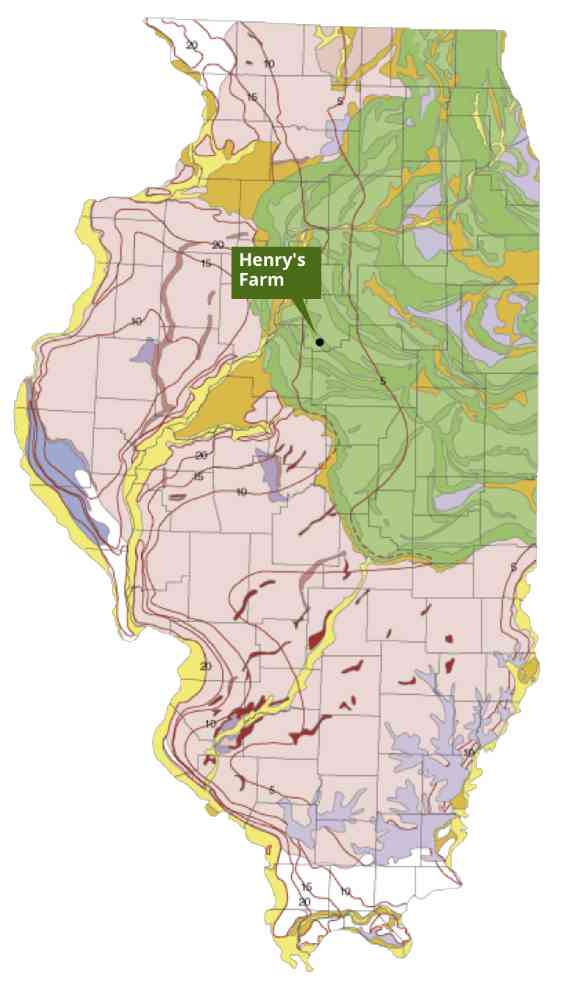

Flat land is much easier to farm using industrial methods than hilly land. And Henry’s Farm is hilly, thanks to glaciers that, from 1,500,000 to 10,000 years ago created ridges and plains as they repeatedly advanced to the south, paused creating a ridge at its edge, and retreated. In the map of Illinois to the left the green area shows alternating bands of ridges (darker) and plains (lighter) left from glacial activity during the Wisconsin Episode. Henry's Farm on one of the ridges.

Rich, deep soil

The soil on Henry's Farm is extremely fertile: a key factor in the taste and level of nutrition of the vegetables he grows and brings to market. When Henry began farming here, he was blessed with rich deep soil because the farm is along Walnut Creek in the Mackinaw River Valley, where periodic flooding has deposited nutrient-rich silt creating richer and richer soil for 10,000 years.

The millennia of soil deposits have created topsoil so deep that Henry's never reached the bottom of it, even when digging down five feet to loosen the burdock roots. Henry works hard to replace nutrients removed from the soil in the form of vegetables taken to market. He continually enhances the fertility of the soil by growing cover crops, rotating crops, returning all plant organic matter to the soil, and leaving fields fallow.

About Henry

“I became a farmer,” Henry states, “because it was the only thing that made sense. I feed my family and other families without hurting the environment; I grow delicious and healthy food for people, and my kids know that when it’s hot, you sweat and when it rains, you get wet.”

After many years living in other cultures (Israel, Japan, Nepal, and Japan again), Henry realized that what was important was a simple, honest living that respected the earth and contributed to the health and well-being of others, “be they humans or rabbits, earthworms or soil microbes, oak trees or algae.”

Henry made the decision to make organic farming his life’s work while still in Japan. That’s where he met his wife, Hiroko, where they were married, and where, in 1990, their first child was born.

When they came back to the U.S. they lived for a year in New York State where they apprenticed with John Gorzynski, who grows organic vegetables for New York City’s flagship Green Market in Union Square.

Henry was uncertain as to where his farming future would be. Then one day, on a trip to visit the family back in Congerville, Henry had an epiphany. He stuck a shovel into the earth, just as he had been doing in New York, and turned it over. For a long moment, he stared at the incredibly rich, black, loamy earth. That was it. He knew that this was where he had to be; this was the land he would farm.

And that’s what Henry has been doing since 1993, building the soil, planting hundreds of kinds of vegetables, and enriching the lives of every person who eats them.

Along the way he has spoken at many winter farming conferences, and won many awards, including the R.J. Vollmer Sustainable Agriculture Award and the prestigious USDA Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Patrick Madden Award.

Henry’s Farm Apprenticeships

The Hanging at Henry’s Video Blog

Please read the following before applying for an apprenticeship

The Work

The basic categories of work are planting and transplanting, weeding, mulching, harvesting and selling. Almost all of the work is done by hand or with hand tools. I have one small tractor for tilling, making beds and some cultivation.

A day on the farm is long, hot and hard—full of sweat, pain and bugs. I love it. But most people don't. I once had someone quit after three hours and never come back. I have also had apprentices who decided to stay on for another year. One former apprentice stayed on as my farmhand and has been here for over 12 years now.

A season on the farm should feel like time spent in a foreign country. It should feel like a completely new environment. You will make the shift from a consumer of food to a producer of food. There is so much to learn, to observe, to absorb. There are the details, a rainshower of details—how to wield a hoe, how big to make a bunch of carrots, how far apart to thin the lettuce, how thick to lay the mulch, which is the tatsoi and which is the mei qing choi. The details, while overwhelming in sheer number, are relatively easy to learn and easy to teach.

Then there is the overall picture. The overall picture is harder to grasp and perhaps impossible to teach. Understanding the overall picture means having a feel for the weather, the seasons, the soil, the landscape. It means having a feel for the way nature works. Actually, I don't know what understanding the overall picture means. It is impossible to explain. The only way I know to learn about it is to become part of it. When you wake up with birds singing in the predawn and go to bed when it gets dark; when you are exposed day-long to the elements; when you are wet when it rains, oily with sweat when it is hot, shivering when it is cold; when your hands are stained with soil; when you eat what you grow—when you feel the days get longer and longer and then shorter and shorter—then you start to get a feel for the overall picture.

The basic categories of work are planting and transplanting, weeding, mulching, harvesting and selling. Almost all of the work is done by hand or with hand tools. I have one small tractor for tilling, making beds and some cultivation.

A day on the farm is long, hot and hard—full of sweat, pain and bugs. I love it. But most people don't. I once had someone quit after three hours and never come back. I have also had apprentices who decided to stay on for another year. One former apprentice stayed on as my farmhand and has been here for over 12 years now.

A season on the farm should feel like time spent in a foreign country. It should feel like a completely new environment. You will make the shift from a consumer of food to a producer of food. There is so much to learn, to observe, to absorb. There are the details, a rainshower of details--how to wield a hoe, how big to make a bunch of carrots, how far apart to thin the lettuce, how thick to lay the mulch, which is the tatsoi and which is the mei qing choi. The details, while overwhelming in sheer number, are relatively easy to learn and easy to teach.

Then there is the overall picture. The overall picture is harder to grasp and perhaps impossible to teach. Understanding the overall picture means having a feel for the weather, the seasons, the soil, the landscape. It means having a feel for the way nature works. Actually, I don't know what understanding the overall picture means. It is impossible to explain. The only way I know to learn about it is to become part of it. When you wake up with birds singing in the predawn and go to bed when it gets dark; when you are exposed day-long to the elements; when you are wet when it rains, oily with sweat when it is hot, shivering when it is cold; when your hands are stained with soil; when you eat what you grow--when you feel the days get longer and longer and then shorter and shorter--then you start to get a feel for the overall picture.

Our Relationship

My idea of the ideal relationship between an apprentice and farmer is one where the apprentice asks the farmer as many questions as they have. Why do you do it this way? What happens if you do it this way instead? What happens next?

Just as important as asking questions, however, is watching the farmer closely and trying to learn as much as possible just from observing him. You will be doing new and different tasks almost every day for the entire time you are here. I, on the other hand, will be doing tasks that I have done so many times that they are (sometimes) second nature to me. If the way I do something doesn't make sense to you, ask me about it. Chances are that I have a reason for doing it that way (although sometimes it is hard for me to remember what the reason was).

The other thing that you as an apprentice should be trying to learn is whether the farming life is for you. I can't help you there except by giving you the total immersion experience. By the time you leave here, you will have become an integral part of this farm.

The Hours

Monday-Thursday

The apprentice's day runs from 6 in the morning until 6 in the evening, with a 2-hour break for lunch and rest during the hottest part of the day.

Friday

The big harvest day. We start at daybreak and stop when everything is picked, with only a short break for lunch.

Saturday

Market day in Evanston. We leave the farm at around 1 in the morning and return around 5:30 p.m.

Days off

Saturday and Sunday, unless you helped out at the market on Saturday, in which case you get Sunday and Monday off.

Compensation

Apprentices are provided with free lodging in a 14 x 60 foot mobile home located on the farm. The home has a full kitchen, bathroom, living room and three bedrooms. You will share the home with the other apprentices.

The apprenticeship is meant to be a learning and training experience, not a job. As such, you won't be paid wages. You will receive a stipend every week, which should cover your living expenses while you are here. Housing is free (you won’t pay for rent, utilities, repairs, etc.) and your food bill should be next to nothing as you’ll get all the vegetables you can eat as well as any fruit, meat, grains and eggs that we grow for our own use.

Farm Rules

- No smoking or drinking during work hours or break times.

- No smoking in the house.

- Lateness to work is not tolerated. (Every minute counts.)

- You are expected to work as hard and fast as you can all the time. Everybody on the farm (from our youngest apprentice to our 80-year-old parents to the family dog) works as hard as they are able.